At times, it felt like I would never finish this. Below is the draft for all of the text for Book Two. I have already begun planning the illustrations, and will post them in the coming weeks. Please forgive any errors. The editing process is, as ever, ongoing. And as always, input, critiques, suggestions, and general moral support are welcome. Just, if you’re going to tell me I’ve got it all wrong, please be gentle. 🙂

1.

Guten Morgen, class. This week, we will be talking about the theory of war. We will be talking about how we define and classify the art of war and the science of war, and how we develop and study and analyze the theory of war. You must please listen very carefully to be sure that you understand. Some of this is quite hard to explain.

War is fighting. However much the methods of doing so might change, that fact remains. The art of war is the conduct of war – Yes, Otter?

-My father said my conduct grade on my report card would be better if I would stop asking so many questions all the time.

Ah. Well, that is a slightly different, er, that is to say…Conduct is behavior, in a way. It is from the Latin conducere, meaning to bring together. The grade on your report card is referring to the way you comport yourself, or bring yourself together, in a sense. What I am talking about is bringing together the elements needed for war, and carrying them out. Does anyone have any ideas what this might include? What might you need? … Yes, Mouse?

– Your fighting forces.

Good! Good. Yes. This is of course the central element. And what do we do with our fighting forces once we have them? Anyone? Boar.

– Train them?

Excellent, yes. And what else might our forces need? Ibex? You have been very quiet. Do you have any ideas?

– Um…w-w-, uh, weapons?

Yes, weapons. Armaments and equipment. So the conduct of war includes raising our fighting force, training and equipping them, as well as fighting.

There are two main categories in the conduct of war. The first is called Tactics. Tactics is planning and carrying out engagements – battles, missions.

The second is strategy. Strategy is how we use all of these engagements together, and how they help us to reach our goals in the war, and ultimately our end in the war.

Tactics and strategy are closely related, and are both in use at the same time, but they are distinct, different.

We can divide the things people do around war into two big categories: preparation – or getting ready – for war, and war proper. We are talking mostly about the second, essentially the use of the fighting force. The other category is made up of things like supplies, medical support, and cleaning and replacing supplies and equipment.

Can anyone think of anything besides fighting that we might consider part of war proper? … No one? Alright, class. I will list some activities, and I want you to tell me whether you think they are part of war or preparation. First, supplies. We just talked about that. Marten?

-Preparation.

Yes, good. Fox, camps and billets. These are places to rest during war, during breaks in engagements. To which category do these belong?

– War?

Yes. Why?

– I don’t know. I mean, because it’s not before you fight. It’s in between fights, so you’re not preparing. You’re already in war.

Partly right. Camps and billets are part of war proper, but it is because we apply tactics and strategy to them – where we rest, for how long, how we set up the camp, and the fact that when we are in camp, we are still ready to fight.

Bear, what about marches, the movement of our fighting forces?

– Preparation?

Nein. Sometimes we march during an engagement. Even when we are just on our way to an anticipated – Yes, Otter?

-What does ‘anticipated’ mean?

Expected. When you anticipate something, you expect that it will happen, you are predicting that it will happen.

Even when we are just on our way to an engagement, we must be ready to engage at any time, the way we line up, which forces go where. We are also strategic in the routes we take. With every choice we make about when and where and how we march, we are considering strategy and tactics. If we came upon our enemy, would we prefer to be on the near or far side of this river, or this chain of hills? Would we rather be up on that ridge, or on the road? Would it be best to travel in one large column, or several smaller ones? Yes? Any questions, class? … Otter? Is something the matter? You look as though you will maybe explode.

– N-no, sir. Fine, sir.

Otter? Ah. Your father was quite wrong, you know. How are we to learn if we don’t ask questions?

– Just. Just, what’re the answers?

What are what answers, Otter?

– To those questions. The ones you just asked. About the hills. And the road and the columns and the river.

Ah, well, that depends on the situation. There is no one right answer to any of those questions. It depends on how you want to use your forces, what you anticipate from your enemy, a number of things.

———

2.

For today’s class, we will be discussing the theory of war.

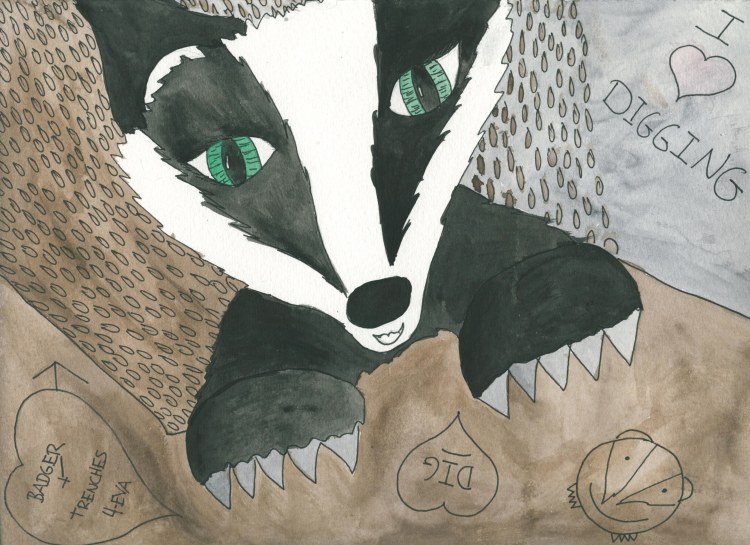

The term ‘art of war’ originally did not mean what it means now. It only meant the preparation: producing weapons, building fortifications, that sort of thing. Who knows what fortifications are, class? Yes, Badger?

Walls, trenches, things like that?

Yes. Good, Badger. Fortifications are how we make our position stronger, things just like that. Siege warfare was the first true — Yes, Otter?

– What’s ‘siege’ mean?

Siege warfare is when one side is defending a set position, like a castle, or a town, and the other side closes them in to try to make them give up. Yes?

– Yes, Sir. Thank you, Sir.

So siege warfare was the first true war, the first kind of war where you can see operations, planning, thought. Then some people started converting tactics into systems. This was a step toward an art of war, but there was no creativity to it. It made everyone like robots, following very precise formations and orders. No one thought the conduct of war was something you could make a theory about; it was thought to be something that just had to happen as it happened.

As time went on and people thought about the conduct of war more, we came to need a set of rules under which to think about it. It was so complicated, there were so many parts to it, that early on everyone focused on physical things: numbers of troops, supplies, the size of your base, the angles of attack. They took things they could make into math and based all of the theories on those things. Can anyone tell me what’s wrong with this approach? Yes, Quail?

– War is not all math.

Agreed, but please elaborate.

– Things are mixed up. The largest army doesn’t always win. The people matter, too, and how they feel, and how smart the commander is, and how brave the troops are. Stuff like that.

Very well said, Quail. War is psychological – of the mind – as well as physical. Both sides have a say in the war; it is not just one army doing to another.

A theory of war must consider moral values, as well as physical ones, the way participants think and feel and react. Yes, Otter?

– Well, but…Sir, those are all different all the time, aren’t they? How do you make rules about that?

A very good question, Otter. You are right that moral values change, are different at different times, but there are some effects which are common enough, that we have seen often enough, to make rules about them. And remember, none of these rules will be true 100% of the time. We try to make rules that will be the most right, but leave our minds open to them being wrong. I know it’s confusing, but the role of chance and fluctuation – change – must always be considered.

Now, class, I want to talk about some of those things that matter in war that are more about feelings and reactions, and not so much about numbers and things.

First of all, there are hostile feelings: anger, dislike, hatred. Sometimes these bad feelings are just between countries, not people. If you don’t feel them to begin a war, the fighting will stir these feelings up. Fighting will also bring out other feelings: love of power, ambition, things like that. Yes, Otter?

– What does ‘ambition’ mean?

A desire to be great, a determination to be successful.

– Is it bad?

No, Quail…No, ambition is not necessarily bad. But it can go too far. If you put your ambition ahead of everything else, that can be a bad thing. For a commander to be ambitious is fine, but he must always put the ultimate ends of the war ahead of any feelings of his own. Yes?

– Yes, Sir.

We have spoken before about the dangers of war. We must remember to consider danger when creating a theory of war. For the commander, it is not just her own danger. She also knows that all of her choices will put others in danger. There is no action in war where there is no danger. This is a hard burden, and not everyone can handle it.

While all commanders must possess a certain brilliance and strength, they will not all be the same. The different personalities of commanders will lead to different strategies, different ‘roads’ to our goal, if you will.

In response to danger, there is also courage, bravery, the feeling that allows us to overcome our fear of danger.

People still have all the same regular feelings in war, too: anger, pride, envy, generosity, compassion…anything you can think of. Any questions? Yes, Ibex?

– What about happiness? Can people still feel happy?

Yes, Ibex, even happiness. It might seem strange. When you think of war, you might think of hurt and death and things that make you sad or angry. But people still feel all feelings. They feel sad and angry, but they also laugh and love their brothers.

We also need to remember the enemy. We will never just be doing something alone. In war, there is an enemy, and they have their own soldiers and commanders and feelings and strategies, and much as we will try to predict what they will do, we will not always be able to. Whatever we do, they will respond, and sometimes they will do something and we will need to respond.

Next we must consider the fact that all information in war is unreliable. We can never be sure what is true. We must trust to luck or talent to carry us through. There is no model we can build which can fully overcome this.

Some other things to remember: Things are simpler in the lower ranks, more complex the higher you go. Also, the more physical the task, the simpler it is to theorize: tactics will be much easier to deal with in theory than strategy. And – this is very important to understand, so please let me know if I am not being clear – theory does not have to be a manual, like the book of instructions you get to build a toy or a piece of furniture. Theory is about study, making yourself familiar enough to be able to use it to analyze, detangle, illuminate, define ends. It should be a guide to learn about war. If we think in terms of a guide to our travels, not a precise path, then it is possible to have a theory of war.

Does everyone understand?

– Yes, Herr Clausewitz!

Good! Now, theory studies the nature of ends and means. Our end is victory. Our means are tactics, which will vary depending on what kind of victory we seek. Some of the things we must consider when choosing our means are terrain – where you are, who lives there, whether there are mountains, rivers, swamps, forests, etc. – time of day, and weather, although only fog will really make a difference most of the time. Yes, Bear?

– What about if it’s raining?

Rain might make you a bit uncomfortable, but it will not change what you are doing.

– What if it’s snowing out?

Snow might slow you down a bit, but it will not make a big difference either. In any case, the original — Yes, Bear?

– What if it’s snowing really, really hard, like it’s a huge blizzard and you can’t see and the snow covers the windows of your house?

I suppose I will have to concede, Bear, that that might make a difference, or at least cause us to postpone our actions. OK?

– Yes, Sir.

Where was I? Oh yes. We use tactical victories as our means toward the end of peace. So our strategy consists of planned battles, engagements, and winning them brings us closer to peace. For a good strategy, we will learn these possible means from experience. If we look to history as our guide, we are less likely to get too fanciful, too far from reality, in our thinking. Yes, Marten?

– I thought you said before that it’s good to use our imaginations.

That is a good point, Marten. It is good to use your imagination, to be creative, but it’s best if we base our creativity on understanding what has happened and what it possible. If the only plans you can make are impossible to carry out, it won’t do any good. Does that make sense?

– I think so, Sir.

Theory should only study means as far as they will matter in practice. For example, it is important to know the range and effectiveness of a weapon – how far it can strike and what kind of damage it can do – but not how it is made. Yes, Boar?

– But doesn’t how it’s made effect how it works?

Yes, but the only thing that’s important to you as commander is that it does work. If you know that it works, you personally don’t have to know why.

This is an important point. It is important to simplify the knowledge of the commander. One who is too obsessed with details will not be a good commander. In the past, people thought this meant that only genius could make a good commander, and no theory could help, but it’s like the expression, ‘Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.’ You don’t have to get rid of everything in order to rid yourself of the unnecessary things. It’s not that a commander needs to know no details, just that he needs to know only those things which directly matter in the conduct of the war.

Your responsibilities in war will determine what knowledge you need, and much is up to judgment, not study. You don’t need to be an historian, but know history. You don’t need to be a pundit, but know politics. You don’t need to be a mechanic, but know how far your machinery can go under given conditions. You must absorb this knowledge, so it is a part of you, so that when the time comes to make a decision, you aren’t considering lists of memorized facts, but can make the decision instantly.

So, class, we have split the conduct of war into two fields, tactics and strategy. Tactics have mainly to do with material factors – men, movements, means – and since strategy deals with ends that will lead to peace, the possible factors are endless, so strategy will present the greatest challenge, it will be the hardest to understand in a theory of war. Strategy is mainly the chief commander’s job. For theory, we can concentrate on material and psychological factors – means, and feelings, responses, and such. If this theory can give a commander enough insights, it will smooth her progress and ensure that she never has to abandon her own convictions, beliefs.

———

3.

Now we must decide whether ‘art of war’ or ‘science of war’ is a better term. Let’s look at the two words. In a science, you are trying to find pure knowledge. In art, you need creative ability.

The line between science and art is the line where pure perception ends, and judgment begins. Allow me to explain, Otter. Perception is that which we take in through our senses, what we see, hear, smell, taste. Judgment is what we think about that stuff, what it means to us.

If we think about it like that, ‘art of war’ is probably the better term. Really, war is neither science nor art. It is part of social life, more like commerce – trade, business – than art, and more like politics than either. It does, in fact, as I have said before, come from politics.

I mention this stuff because some question whether war really has general laws, and whether those laws can be useful. I think that it is possible that an inquiring mind – the importance of asking questions, young Otter – can make it clearer and can show at least some of its structure to us. This brings the theory into reality.

———

4.

Today, class, we will be talking about method and routine. There are a few concepts, ideas, that I want to define before having this discussion.

First, law. Law determines action. It is a ‘must.’ A decree or a prohibition is a law. Yes, Badger?

– My Mom said my uncle broke the law and that’s why he had to go to jail.

Er…yes? Well, ah, that is a type of law, so that would be an example we can look at. We have certain laws, and if we break them there are consequences. Sometimes, that means jail. Yes.

Next: principle! A principle is also a sort of law, but not as strict, looser. Some principles are the same for everyone, and some you might only follow yourself.

A rule is also similar to a law, but more flexible. A rule can also be a guideline, a shortcut that helps guide our action such as the rules in board games or some math problems. Can anyone think of a rule like that? Who can tell me a rule of, say, geometry? Mouse?

– A triangle always has three sides.

Yes! Very good, Mouse. A triangle always has three sides. We know that rule, so we know when we see a shape with four sides that it is not a triangle.

We also have regulations and directions, which are used more specifically, for smaller things that don’t require general laws or rules.

Now, a method is a way of doing things. There can be more than one right way to do something. For example, let’s say you want to draw a picture of a face. You can draw the eyes, and then the nose, and then the mouth; or you can draw the mouth, and then the nose, and then the eyes. Either way, when you are finished, you have a picture of a face.

When we repeat a particular method often enough, it becomes a routine. You probably all have routines you follow when getting ready for class in the morning. Otter, do you do certain things each morning to get ready?

– Yes, Sir. Mostly. I get up, and then I wash my face, and then I eat my breakfast, and then I brush my teeth, and then I get dressed.

See, Class? Otter washes his face, then eats his breakfast, then brushes his teeth, then gets dressed. That is his morning routine.

Principles, rules, regulations, and methods will happen often enough that it will be useful to know them, but they will not work in every situation. If the path in front of you is simple and clear, you don’t need to consult a rulebook; you can just follow it.

These guides will be especially useful for those parts of theory that lead to doctrine, so more in the realm of tactics than strategy, as that is the part of the conduct of war most likely to allow for theory to become doctrine.

…

Class, do we all know what ‘doctrine’ means? Fox? Ibex? Mouse? Anyone? I think perhaps I was boring my class to sleep! A doctrine is a set of ideas and instructions that we believe are right. It can be very useful, as long as we do not forget to keep using our brains, too! Yes?

Alright. I will give you an example of a tactical principle: firearms should not be used until they are within effective range, in other words until you are close enough that you have a good chance of hitting your targets with them. That is a simple, sensible principle that it should be both easy and useful to keep in mind.

Regulations and methods belong in a theory of war because they are drilled into troops, and routines have a place as well, as long as we remember that they are not binding, that we are not required to follow them no matter what. They can be especially useful for lower-ranked officers. As we so often don’t entirely know what is going on in war, it can really smooth things to follow routines when what is happening does not require us to do otherwise.

Routines can be overused. Even the highest-ranking officers sometimes get stuck in a routine, if they do not have enough education or experience, staying always with the one or two things they know or perhaps following their supreme commander’s favored approach. This lack of imagination can be deadly.

Consider this: if you have three pets, and all three are goldfish, you can likely take good care of them by cleaning the tank and throwing in some fish food once or twice a day. You might keep them more or less healthy depending on how often you clean the tank, or how much food you give them, but that routine suffices to care for all of them.

However, if you have three pets, but one is a goldfish, one a gerbil, and one a kitten, you cannot simply follow this one routine. You must clean the tank and use fish food for the goldfish, provide fresh bedding and pellets for the gerbil, and give cat food and clean litter to the kitten. If you try to follow the same routine to care for all three pets, your gerbil and kitten will soon die.

Different situations require different solutions, and creativity is especially important in the realm of strategy.

———

5.

Now, class, it is time to talk about critical analysis. I know those are big words, but allow me to explain. Critical analysis is when we take those truths we have figured out using our theory and use them to make sense of actual events.

It is not just about telling what happened. It is doing research, to find the facts of what happened; then finding the causes of what happened; and lastly, judging those events, praising the good decisions and censuring the bad ones.

It can be very hard to find the causes in all the mess and chaos of war, but the important thing is to use care, to trace them as best you can, as far as you can, and to look at all of the different causes, as there is rarely just one.

You must take care, find out as much as you can. What means were used? Did they do as intended? Don’t stop your analysis until you have reached the truth, something that no one can contradict – disagree with.

All of this study will go nowhere if you do not have theory to begin with. If you have theory, and your analysis leads to that theory, then you can conclude your study. If your study seems to go against the theory, that doesn’t mean you need to throw out one or the other. Remember, theory is a guide to help your judgment, not a law that must be followed. There are exceptions to every guideline. Look at the individual case. It might be an exceptional case. Look at the reasons why it does not fit the theory.

The critic’s job is easy when cause and effect, and means and ends, are closely linked. If you line up a row of dominoes and knock the first one over, what will happen, Mouse?

– They’ll all fall down.

Yes, that’s right. If you knock over the first one, the others will fall. That is a simple, immediate cause and effect. But let’s say Fox fails a math test. Was it because he was tired? Because he didn’t study enough the night before? Because he was sick two weeks ago, and missed a class where important information was given? It might be harder to trace the cause in this case.

War is much more often going to be like this. There are many causes to each effect, many means and ends, many things large and small happening all at once, and all are connected, and all have their impact, however small, on the final outcome, and the ultimate end which is, of course, the restoration of peace. Yes, Marten? You have a question?

– If the point of war is to make peace, why do we have a war in the first place? I mean, if we don’t go to war, don’t we already have peace?

This is a good question, Marten, and I understand why that would be confusing. There are a lot of reasons countries go to war. Two countries might be at peace, but one wants more land, or does not like the behavior of the other, or feels that it must protect certain people who live in the other’s territory. There might be religious differences, or one country might have a lot of food while the other goes hungry. The political leaders decide those things, the kings and presidents. It is not for the commander, or the philosopher of war, to decide when we go to war, or why. It is our job simply to understand the conduct of war itself, and the commander’s job to find the best way to wage war in order to make peace in a way that reaches the goals of their country’s political leaders. All I can really say is that while there might be peace before the outbreak of war, it may not be the peace your leaders want.

So cause and effect, means and ends. There are, naturally, some difficulties that arise with causes and effects. The further the cause is from the effect, the more possible causes we have to consider. And the more important the end, the greater the number of means which effect it. Every single person involved in a war is pursuing the final end of peace, so we must consider everything when determining the effects and means which lead to peace. It is easy to get lost in so much information.

For example, in March 1797, the great commander Bonaparte and the Army of Italy left Tagliamento to meet Archduke Charles, hoping to force a decision before the arrival of reinforcements from the Army of the Rhine. Looking at the immediate goal, they chose their means well, and the result reflected this thusly. The Archduke, his forces weakened, made only a token resistance on the Tagliamento. In the face of his enemy’s determination and robustness, he vacated the area and approaches to the Norican–Ah. Right. Sorry, class, I was getting a little carried away.

Let’s see…We’ll look at this on the map. Make sure you can all see. Good? Good. So, Bonaparte’s enemies were the Austrians. He was trying to defeat them before his backups arrived. His forces were strong, and the Austrians were weak, so they quickly ran away. What was the right thing to do at that point? Follow them into Austria, ease the way, then join up with his allies in the Army of the Rhine? That was one means of reaching his end, what he thought was the right one at first.

However, Bonaparte’s bosses back in France knew that the Rhine forces were several weeks away, so that means looked risky. What if the Austrians got reinforcements? They could then not only defeat Bonaparte’s Army of Italy before the Rhine forces could get there, but that could mean losing the whole campaign. Bonaparte figured this out, and signed an armistice – a truce – with the Austrians while he still had the upper hand.

Looking back on that now, though, we have more information than Bonaparte did. We know that the Austrians did not have any backups from the Rhine to Vienna. You see? Bonaparte’s Army was actually a threat to their capital city, so he might have been able to get more from them, depending on how much they valued their capital.

What if he had pursued them to Vienna, here, and they had abandoned it and withdrawn? Then the Rhine forces would have had time to get involved, and France would have had a definite advantage in numbers. Would France then have wanted to keep pursuing until they broke the Austrians completely, wiped them out? Or would they have been happy with a smaller, but still large, gain in territory and a peace agreement?

What if they tried to purse the Austrians further, and found that they did not have the strength to finish the job? If the French spent too many forces taking a few provinces but left themselves weak, Austria could have turned around and beaten them all the way back, like so.

We can be sure that a commander as gifted as Bonaparte considered many of these possibilities when making his decision, and that some of them go to why he decided to sign for peace at that point.

There were two important things he had to consider there.

1) What value the Austrians would place on different outcomes: would they have thought it worth the cost (the cost being the continuation of the war) when they could have peace without losing too much? These are the elements that we always balance when trying to make peace; it’s a matter of the terms being good enough balanced against the costs being too high. This is why in war, we hardly ever try to completely destroy our enemies. Usually, there is a balance of terms and costs that can get peace more easily.

2) Whether the Austrians would even think through all the possibilities. Or would they be too unnerved by the evident strength of the French? It is important to think of things like this, too, because we are always facing an enemy, and their feelings and thoughts and fears will help decide what happens, too.

Now, why do you think I have explained all of this? Badger?

– I…I don’t know, Sir.

Boar? How about you? Any idea why I have spent so long telling you about Bonaparte’s decisions while fighting the Austrians?

– Well, to show us how much stuff there is to think about?

Yes, quite. Well done, Boar. I wanted to give you an example to show you how hard it is to figure out causes and effects and ends and means on a large scale, when we are talking about the end of the war itself. It is not enough to know the theory. To really work your way through all of the pieces, to figure out what’s most important, you must have some natural talent. You have to be able to understand not just what things people actually did, but what things they could have done. It does no good to say that a commander made the wrong move without being able to say what the right move was.

Take another example from Bonaparte: remember what a siege is, class?

– When one side is in one castle or something, and you block ’em in until they give up!

Yes, Mouse. Thank you. Well in 1796, Bonaparte had a siege on the city of Mantua, but he stopped the siege to go fight Wurmser’s army. He fought off every attempt to relieve Mantua after that, but since he pulled his forces out of the siege, supplies and such were able to get through. Mantua, which might have given up in a week if the siege remained in place, lasted six months.

At the time, no one ever would have even considered staying in place and resisting the relieving army while maintaining the siege. If they had stayed in place, it is possible, they would not have even been attacked, but it was so out of fashion that no one would even have thought of it as an option. But you should always keep an open mind. You may reject that option, but you should consider it first.

It’s not enough to say that one way is better; you have to show why it’s better. In the siege of Mantua, Bonaparte’s plan was the one he thought had the best chance of beating the Austrians. This might be true, but it was a minor victory. Maintaining the siege might have given a little smaller chance of success, but was much more likely to keep relief from reaching the city. You have the balance the risks against the rewards. In this case, where you have a more likely but minor victory against a somewhat less likely but more important victory, I think it would have been worth the risk to be bold.

We must use military history when looking at different means. Experience counts for much in the art of war. In looking at history from the present, we will never know all of the little things, the minor points, the feelings, that went into every decision. And we may never have the genius of a Bonaparte. We do, however, have the benefit of knowing how things turned out, of seeing the big picture. We can point out mistakes, while knowing we might have made the same ones, or different ones, ourselves, if we were in the position of the commander.

It seems too simple to say that the outcome can prove whether or not a move was the right one – it would be nice to be able to say that in similar circumstances, there is a right decision and a wrong one – but sometimes this is just how it is. Bonaparte advanced on an enemy capital four times. Three times, it was the right call. The fourth time, it was wrong. How do we know this?

– The outcomes?

Yes, Quail. The outcomes. In all four cases, peace would mean victory for Bonaparte, and not getting that peace would mean defeat. The first three times – Austerlitz, Friedland, and Wagram – he got his peace terms. The fourth time – Moscow – was a most emphatic defeat for Bonaparte. He misjudged his enemy, and payed dearly for it.

Are you all still with me, class? I know this is a lot to understand. Yes?

There is no certainty in war. You are always trying for the most probable success. You try to minimize the role of chance – make it as small as possible – but it always plays a role, and you can bog yourself down if you try too hard to eliminate it. What I’m saying is the course of action with the greatest chance of success is not always the right one. As I mentioned before, when we were talking about the siege of Mantua, sometimes you need to be daring.

The language, the words we use when we study these events and ideas, should be like thinking in war: as simple and natural as possible. When we were talking about the theory of war, we said it should train the commander’s mind, act as a guide, not a rigid system. Critical analysis is the same. We should not overlook the simple and obvious by being too caught up in a set approach. You should follow the natural workings of your mind whenever you can.

You would be surprised by how often people make things more difficult, more complicated than they need to be.

People get stuck in a narrow system of laws that they use for all analysis. Or worse, they use unnecessary jargon – lots of technical terms, big words where small ones would do, coded language where simple would suffice. They use lots of big words and flourishes, which often hide the fact that their arguments are bad or empty. Others will try to show off what they know by listing lots of historical examples, but often misusing them. People will talk about events without really understanding them.

The keys to good analysis are simple. Use plain language. If your thinking is good, and your ideas are strong, simple language will allow them to shine. Observe and study to understand all that you can. Stick to the point. Stay close to those people who actually have to manage things in battle by their wits.

———

6.

For our last lesson about the theory of war, I want to talk a little bit about historical examples.

When you are using examples from history in the theory of war, it is your job to make them clear and to use the ones that give the best proof of what you are saying. It is very easy to use examples incorrectly, to give examples that don’t really support your argument, to misunderstand the importance of an example.

It easy to find examples to support things most people believe anyway. Something works, and it gets used again and again, and becomes common.

We are not content with this though. Sometimes we might need to use examples to prove that the thing most people think is wrong, or to prove that something everyone thinks is wrong is actually right, or to show everyone a new idea.

There are several different ways to use examples:

1) An explanation of an idea – telling what you mean

2) The application of an idea – telling how the idea works

3) To prove the truth of a statement – this is a simple statement of fact. One clear, well-known example is fine.

4) To create a doctrine – Who remembers what ‘doctrine’ means? Fox? Can you help us all remember what doctrine is?

– Um, it’s…directions, or rules – no, instructions. Ideas that we think are right. Right?

Yes, a set of instructions or ideas that we believe are right. Theory can help us create doctrine to follow. Is doctrine the same as a law? Ibex?

– No. It’s a guide, but it’s not always right.

Good. In any case, if you are using example to create docrine, you need a detailed explanation of an event, with other examples to support it, looking at all events and circumstances to show their effects. You need to give as much detail as you can for every example you use, so that it is quite clear that you are right. If you are attempting to create a doctrine with bad information, it will be at best useless and at worst, harmful.

It is best to use as recent examples as possible. With things that happened a long time ago, we don’t know as many details, and stories might have changed in the telling. Also, the more recent the war, the more similar the arms and tactics and such will be.

It would be wonderful to teach the art of war entirely through the examples of history, but that is a huge task. It would take incredible time, effort, experience, and dedication to the truth, the whole truth with no vanity or modesty. This is the work of a lifetime.